Will “Political Procrastination” Undermine Irish Climate Leadership?

Written by Joseph Curtin, Senior Research Fellow, IIEA

Pat Cox, former President of the European Parliament, offered some interesting observations on Irish efforts to grapple with climate change in a speech delivered to the Chartered Accountants Ireland Annual Dinner on 7 February 2019.

One topic he touched upon was “political procrastination”, following a report in The Irish Times that government might postpone the implementation of its long-awaited climate plan in the event of a no-deal Brexit. “Planning continues but action may be paused” in this scenario, according to Mr Cox.

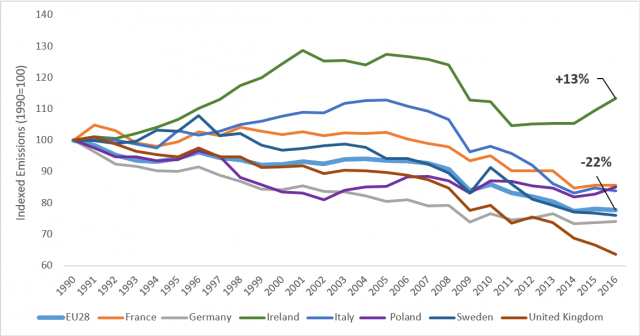

The wider context for his remarks is Ireland’s lacklustre climate performance over several decades. Since we have become unequivocally aware that climate change will cause severe, widespread and irreversible damage to lives, livelihoods and the natural environment in about 1990, the EU has managed to reduce emissions by 22%. By contrast, Ireland’s emissions have increased 13% (Fig 1). While our European partners have been getting on with the hard work of decarbonisation, successive Governments have failed to show much interest at home, while touting “Irish leadership” to our EU and UN partners.

Figure 1. Ireland’s emissions performance compared to EU average and other Member States

Previous climate strategies, published in 2000 and 2007, were ambitious and forward-looking, but implementation was patchy. When the 2007 plan elapsed, we waited almost five years for the next strategy to be published, and when it finally was in 2017, it was underwhelming. By its own admission, full implementation of all the measures would have left a gap to target of tens of millions of tonnes of emissions by 2030. Little additional clarity was provided in the most important areas (peat, coal, renewables, battery, deep retrofit, electricity storage technologies etc.) and few new and substantive measures were announced.

But then something changed. First, the National Development Plan was published in February 2018. It earmarked €21.8 billion (€7.6 billion Exchequer/€14.2 billion non-Exchequer) of investment capital for low-carbon transition and established several ambitious targets including: upgrades of 30,000 to 45,000 residential properties per annum to a minimum “B” BER (and similar for non-residential buildings); 4,500 megawatts of additional renewable electricity by 2030, and new support schemes for renewable heat and electricity; at least 500,000 electric vehicles on the road by 2030 with additional charging infrastructure; and an increase in energy research funding, etc. These were properly ambitious commitments attached to funding streams.

Then Richard Bruton T.D. was appointed Minister for Communications, Climate Action and Environment in October 2018. He promised to “make Ireland a leader in responding to climate change, not a follower”, which he acknowledged would require “a significant step change across government” and since then he has shown every sign that he will make good on this promise.

Was Ireland, finally, going to get to grips with its climate commitments? It certainly looked that way. Early last month, Minister Bruton proposed to a Cabinet sub-committee that each key Department would have to achieve specific targets - an approach proposed by the IIEA, and a marker of serious intent. This new plan was anticipated by the end of March 2019. In a parallel process, the Climate Action Committee has also been making good progress, with a high degree of political consensus emerging on some issues.

Which brings us back to “political procrastination”. We in Ireland have found innumerable reasons to pause decarbonisation over the past two decades. Either the economy was growing too fast to meet targets, or recession had deprived us of investment capital, or Ireland’s emissions profile was “unique”, or Ireland’s target was too ambitious, imposed by faceless Brussels bureaucrats. As Ireland’s circumstances changed, so too did the excuses.

The latest reason for delay, according to a source speaking to The Irish Times, is that there are “concerns that a big move now on climate when the farmers are facing a potential Brexit apocalypse mightn’t be the wisest thing politically”.

However, the strategic implications of Brexit can be interpreted in various different ways. One could just as easily argue that the best time to introduce targets to reduce emissions is when they are already falling; or that a hard Brexit enhances the logic for rapid decarbonisation, creating yet another reason to move away from importing fossil fuels via increasingly precarious UK pipelines. And, as Mr Cox remarked, yet another pause, “would be a dereliction of our national responsibilities to ourselves, our rising and future generations, to the wider world”.

Brexit and climate change are like apples and tomatoes—there is no reason to mix them. To do so is to perpetuate the false dichotomy that we must choose between the economy and the environment when, in reality, there are no jobs on a dead planet. It is perhaps time to take our cue from the next generation, and to listen to young protestors like Saoi O’Connor (16) from Skibbereen Community College, who will gather on 15 March 2019 to remind us: “if we don’t fix global climate change, there is no point in us going to school”. As Greta Thunberg says, there is no point in learning facts if governments keep ignoring them. Hard, soft or no Brexit, hopefully the positive signs of Irish climate leadership from the past year will not fall victim to “political procrastination”. Pressing pause again is not an option.