What are the implications of the Dutch parliamentary election results for Ireland and the EU?

Author: Alexander Conway

Author: Alexander Conway

Introduction

Background

The Netherlands held its scheduled national elections for the 150 seats of the Tweede Kamer (Parliament) on 15-17 March 2021. Ahead of the elections, the centre-right coalition government, led by Prime Minister Mark Rutte, resigned on 15 January 2021 over the toeslagenaffaire, an investigation into false allegations of childcare benefits fraud which targeted dual-nationals and Dutch citizens with immigrant backgrounds. In the interim, Mr. Rutte led a caretaker government of the previous coalition managing the Netherlands’ COVID-19 response.

Since the Brexit referendum in 2016, the Netherlands’ position within the EU has shifted towards filling the liberal free-trade gap left by London’s absence as the nominal leader of the “Frugal Four”, and its transition from the ‘largest small country’, to the ‘smallest large country’ in the Union. The Netherlands is an influential Member State, and key ally of Ireland on several portfolios including digital taxation, trade, competitiveness and economic reform of the Single Market. A change in the Netherlands’ EU positions could have wide-reaching effects for the Union, and for Ireland’s place within it.

The election could be considered a referendum on Mr. Rutte’s leadership and the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, although it was not a major feature of the campaign. The election took place against a backdrop of protests and riots against the government’s handling of COVID-19, especially the imposition of a curfew, which led to attacks against testing and vaccination centres as well as the toeslagenaffaire scandal and farmers’ protests against nitrogen emissions restrictions.

The Tweede Kamer has 150 seats, 76 of which are required to form a majority government. No party has achieved an outright majority in over a century and this has contributed to the Dutch political tradition poldermodel of consensus-based policy-making coalitions. The entire country forms a single nationwide constituency within a pure proportional representative system, with 0.67% of the national vote required to win a seat. This contributes to significant political fragmentation with 17 parties holding at least one seat. On this occasion, voters cast their ballots over a period of three days, due to COVID-19 restrictions, with a turnout of 82.6%, the highest since 1986.

Results

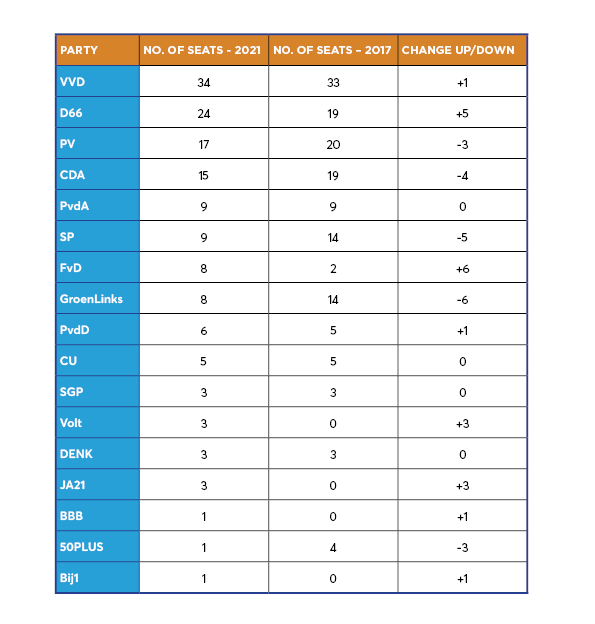

Mark Rutte’s centrist Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) was the clear winner of the election, gaining an extra seat compared to 2017, and Mr. Rutte will probably continue as Prime Minister for a fourth term, and would become the longest serving Prime Minister in the history of the Netherlands, should he be still in office by August 2021.

The results were disappointing for left-wing parties: the Labour Party (PvdA) remained stable with nine seats; the Green Left (GroenLinks) lost just under half of their 14 seats; the Socialist Party (SP) went from 14 to nine seats; and the Party for the Animals (PvvD) held their six seats. The centrist-liberal party D66 appears to have been the primary beneficiary of the declining support for the left-wing parties. D66 gained five seats to become the second largest party with 24 seats. The centre-right Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) had a poor result, losing four seats of 19, and party leader Wopke Hoekstra may possibly be leaving the Finance Ministry, which is traditionally held by the second largest coalition party. This could potentially trigger a leadership challenge. The two traditionally Christian conservative parties, Christian Union (CU) and the Reformed Political Party (SGP) were unchanged, with five and three seats respectively.

The far-right overall won 29 seats, its best ever result, split across several parties. Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV) underperformed and lost three of its 20 seats, while Thierry Baudet’s Forum for Democracy (FvD) gained six seats to eight, while promoting coronavirus conspiracy theories, and despite an anti-Semitism scandal and a party-split. The fractured nature of the far-right and unwillingness of other parties to work with them could mean that their overall political influence may be limited.

Four new parties also entered the Tweede Kamer: far-right JA21, who split from FvD, gained four seats, the pan-European liberal Volt party won three seats, the Farmer-Citizen Movement (BBB) and the anti-racist BIJ1 with one seat each. The DENK party, which aims to represent ethnic minorities in the Netherlands and particularly the sizeable Turko-Dutch community, retained its three seats, while the elderly rights party 50PLUS went from four seats to one.

The next step is the appointment of an informateur (respected elder political figure) by the Tweede Kamer to facilitate coalition negotiations by naming a formateur, usually the leader of the largest party, which in this case is the VVD’s Mark Rutte, to begin talks. The outgoing VVD-CDA-D66-CU coalition government took 225 days to form following the 2017 elections, so the current caretaker arrangement is likely to continue for the foreseeable future until an agreement is reached.

Possible Implications for the EU and Ireland

Based on the preliminary results, a coalition of the VVD, D66 and CDA would fall just short of a majority with 73 seats, so a fourth coalition partner would be necessary. Possible partners include; CU (previous coalition partners), PvdA (who may clash with CDA and would only enter coalition with GroenLinks), the far-right JA21 or pro-EU Volt. Alternatively, if Mr. Rutte wished to work without the CDA, or if they were unwilling to enter government, a possible left-wing coalition could comprise the VVD (34), D66 (24), PvdA (9), GroenLinks (8) and Volt (3), which would have 78 seats. A five party coalition, however, could potentially prove unwieldy.

While the ultimate coalition make-up is still unknown, the possible permutations based on election manifestos, all seem to indicate that any future Dutch government could take a softer line on EU fiscal measures efforts and be less “frugal” given the large government interventions due to COVID-19. This is especially true with the openly pro-EU D66 candidate likely to take over the Finance Ministry, which traditionally leads Dutch European policy. D66’s strong performance will likely influence any future coalition to take a stronger stance on green and sustainability issues. While the EU was not a major feature of the election, as evidenced by the #EUOlifant campaign, the result exposes a potential fracture within Dutch politics. The divide is not so much right versus left, but between broadly pro-EU and eurosceptic positions. The success of the eurosceptic FvD and pan-European party Volt as well as the relative decline of left-wing parties are emblematic of this shift.

In terms of Ireland’s interests, the Dutch election will likely change little about Dutch policy positions on the European stage, although a more pragmatic Dutch stance towards European fiscal or economic integration may lessen opposition to possible future Stability and Growth Pact reforms, especially given Mario Draghi’s appointment as Italian Prime Minister. The potential replacement of CDA leader Mr. Hoekstra may improve Dutch relations with southern and eastern Member States, given his controversial statements during EU budget negotiations. Dutch scepticism towards enlargement is unlikely to change significantly, while the Netherlands’ position is leaning increasingly towards France on more robust trade enforcement policies to address uncompetitive practices or deregulation. EU rule of law concerns will remain central for the Netherlands, like Ireland, with a more left-oriented Dutch coalition government likely to place a greater emphasis on tying receipt of EU funding to respect for EU values, like democracy and LGBT rights, rather than focussing on budget mismanagement for countries like Hungary and Poland.

While the face of Dutch politics may not change, underneath the surface a more liberal coalition could signal a shift towards a less fiscally austere, more green, sustainable and constructive partner for like-minded countries like Ireland within the EU.