The Gray Zone: Ireland in an Era of Renewed Great Power Competition

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a watershed moment in modern European history, and is considered by some to have marked the end of the ‘post-cold war era.’ As the geopolitical environment evolves, it will likely be increasingly marked by great power competition. Russia, alongside others, are already deploying a diverse suite of tools including cyber-attacks, information warfare, economic warfare, energy market manipulation, and, as occurred off the southwest coast of Ireland on 03 February 2022, high-profile military exercises as a show of force. Seeking to avoid escalations which may trigger large scale warfare between NATO and Russia, these tools, commonly referred to as threats residing within the ‘Gray Zone’, have become the preferred modus operandi for the Russian Federation in achieving its political and military objectives. The Russian naval exercise episode illustrates that Ireland is not removed from these global developments and has raised questions about the Irish state’s ability to counter such threats.

The Gray Zone: Geostrategic Competition in the Space Between Peace and War

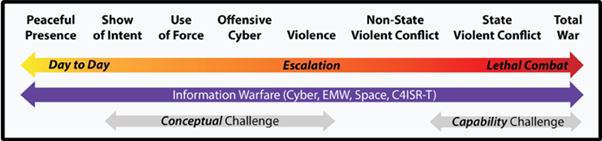

The 03 February Naval exercise exists in a long-running pattern of Russian activity in what has been termed the ‘Gray Zone.’[i] The Gray Zone, or inter-state conflict that exists below the threshold of war, has become the primary space where geostrategic competition now manifests. While this form of sub-threshold competition is by no means a novel phenomenon,[ii] technological innovations and the interconnectedness of the 21st century world has given the use of sub-threshold strategies a historically unprecedented power and viability as a form of inter-state competition, ostensibly while offsetting the risk of triggering a full-scale war.

In their White Paper on the Gray Zone, United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) observed that ‘the post-WWII international system’ we inhabit ‘was established by and to the advantage of’ the West. In response, Russia, often described as a ‘measured revisionist,’ is engaging in a systemic campaign to alter the geostrategic order. ‘Measured revisionists’, in the authors’ estimation, are states who are dissatisfied with the present geopolitical system and work to tilt it in their favour.[iii] As the economic and political cost of major aggression has become so severe, as the ongoing Russian sanctions have shown, measured revisionists have come to rely on the use of incremental steps to secure strategic leverage.[iv] This is often twinned with an avoidance of, but - as we have seen in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine - not a complete rejection, of ‘outright military adventurism.’[v] Such gradualist strategies often use a range of hybrid instruments from coercive diplomacy, propaganda, and information operations, cyberattacks, military manoeuvres, and implied nuclear and other threats.[vi]

Though none of the individual tactics of incrementalism alone could be viewed as a legitimate Casus Belli (i.e. a justification for war), their compounding effects are intended to change the international system in favour of Russia. The use of strategic incrementalism and hybrid tactics enable measured revisionists to amplify their relative power in a form of geopolitical insurgency to make maximum use of the limited military, diplomatic and financial resources available to them.

Credit: US Naval Institute.

Ireland in the Gray Zone

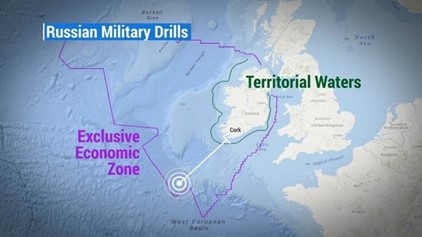

On the 22 January 2022, the Russian Navy announced that it planned to conduct surface gun exercises off the southwest coast of Ireland. The Irish Defence Forces and the Department of Foreign Affairs had been notified by Russian Ambassador to Ireland Yuri Filatov that the exercise would consist of ‘three or four ships.’ The exercises were to take place in Ireland’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), an area Ireland has exclusive rights to, stretching some 200 miles from the shoreline. In the end, the exercise was moved, according to Mr Filatov, so as not to ‘hinder fishing activities.’

Credit: RTE News

Despite the relocation of the exercises to just beyond Ireland’s EEZ, the episode has signalled how Ireland is being drawn into a geopolitical context with which it is unfamiliar. In the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, and threatening postures by the Kremlin towards other non-militarily aligned states in the EU, questions have been raised about the nature of Ireland’s approach to national defence and its positioning in a new epoch of geostrategic competition. Indeed, as the 2022 Commission on the Defence Forces Report (CoDF) has recently highlighted, Ireland is entering into an era characterised by intensifying Great Power Competition,[vii] yet is simultaneously ‘without a credible military capability to protect Ireland, its people and its resources.’[viii]

The 3 February Russian Naval exercise was driven by a range of possible motives and was likely not solely intended to intimidate the Irish state. In one reading, it could be interpreted as simultaneously sending a message to the EU and to NATO that Europe’s western flank is vulnerable - an act of strategic intimidation, intended to undermine the EU and NATO’s confidence in their own security. This was likely done in the hope of tempering the responses to the Russian military activities in Eastern Europe, which ultimately escalated to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Moreover, the decision to conduct the exercise over a chokepoint of the strategically significant transatlantic communications cables connecting Europe with North America, as shown in the diagram below, highlights the potentially critical vulnerability of electronic communications infrastructure in the North Atlantic in the event of an escalation in the war in Ukraine.

Map of Transatlantic Communication Cables with the Original Location of the 3 February Russian Naval Exercise overlayed, source The Irish Times.

The reality of Ireland’s security situation is that, due to its lack of military capacity, the country is unable to counter these forms of hybrid strategies effectively. Indeed, Ireland’s capability limitations, such as its lack of primary and coastal radar systems,[ix] have, according to the Commission on the Defence Forces, left the Defence Forces ‘unable to conduct a meaningful defence of the state against a sustained act of aggression from a conventional military.’[x] Ireland’s Minister for Foreign Affairs and Minister for Defence Simon Coveney, who endorsed the Commission‘s report, acknowledges that Ireland does not ‘have the power to prevent [the exercises from] happening.’. At a webinar hosted by the IIEA on 02 February 2022, Vice Admiral (Ret.) Mark Mellett noted how, in the context of the planned military exercises, ‘the Russian Federation was able to declare it was going to annex 5,000 kilometres where [Ireland has] sovereign rights for five days.’ With this in mind, Michael Mazzar, writing on geostrategic competition in the Gray Zone, has observed that Russian Gray Zone activity is often framed to ‘convey political messages’ about the inability of the target government to safeguard its citizens[xi]. The Russian Naval Exercise’s generation of a flurry of articles in international media, such as for example The Times of London’s piece, entitled Kremlin Homes in on EU’s Weak Link, play into Russian Information Warfare strategies, amplifying, enhancing, and augmenting the ability of the Russian state to engage in activities of intimidation and coercion. Thus, in exposing and, to an extent, publicising Western Europe’s so-called ‘weak link’, Ireland’s security deficits had been instrumentalised as a means of projecting Russian power.

Conclusion: Ireland is no longer insulated by insularity

If Ireland wishes to remain secure it will likely have to rethink its approach to national defence to adapt to the 21st century security environment. Most importantly, the conventional belief that Ireland is protected by geography or by virtue of its non-aligned status, has been increasingly called into question. The fact that Ireland plays host to Europe's largest data-hosting cluster, with approximately 30% of the European market, may also change the type and intensity of threats the state faces.

Indeed, the Commission on the Defence Forces has already highlighted that Ireland can expect to face a ‘growing risk’ of becoming a target of hybrid aggression.[xii] Likewise, Ireland is exposed to the threat of its land, air, maritime and cyber domains becoming ‘vectors of attack’ on Ireland’s neighbours and partners.[xiii] By carrying out these naval exercises, Ireland’s defence policies and its non-aligned nature were possibly instrumentalised and weaponised by the Russian State as a means of enhancing and projecting its own relative power, and its own perceived strategic leverage over the EU. This poses a threat both to Ireland’s national security, diplomatic relations, and its political interests.

In this light, following the Russian naval exercises of 03 February, Ireland now finds itself being drawn into the realities of great power competition. Though it may be an island, floating in the Atlantic at the farthest edge of Europe, the conditions of the 21st century may require a strengthening of Ireland’s defence capacities in order to withstand the new challenges and threats that the country will no doubt face.

[i] Mazzar 2015: 4 Mastering the Gray Zone: Understanding A Changing Era of Conflict. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College.

[ii] Mazzar 2015: 4 Mastering the Gray Zone: Understanding A Changing Era of Conflict. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College.

[iii]Mazzar 2015: 1 Mastering the Gray Zone: Understanding A Changing Era of Conflict. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College

[iv] Mazzar 2015: 3 Mastering the Gray Zone: Understanding A Changing Era of Conflict. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College

[v] Mazzar 2015: 1 Mastering the Gray Zone: Understanding A Changing Era of Conflict. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College

[vi] Mazzar 2015: 93 Mastering the Gray Zone: Understanding A Changing Era of Conflict. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College.

[vii] Commission on the Defence Forces 2022: 5 Commission on the Defence Forces Report. Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/eb4c0-report-of-the-commission-on-defence-forces/

[viii] Commission on the Defence Forces 2022: 28 Commission on the Defence Forces Report. Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/eb4c0-report-of-the-commission-on-defence-forces/

[ix] Commission on the Defence Forces 2022: v Commission on the Defence Forces Report. Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/eb4c0-report-of-the-commission-on-defence-forces/

[x] Commission on the Defence Forces 2022: 32 Commission on the Defence Forces Report. Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/eb4c0-report-of-the-commission-on-defence-forces/

[xi] Mazzar 2015: 4 Mastering the Gray Zone: Understanding A Changing Era of Conflict. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College

[xii] Commission on the Defence Forces 2022: 7 Commission on the Defence Forces Report. Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/eb4c0-report-of-the-commission-on-defence-forces/

[xiii] Commission on the Defence Forces 2022: 7 Commission on the Defence Forces Report. Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/eb4c0-report-of-the-commission-on-defence-forces/