The Cost of Passivity: Can the Strategic Compass Guide the EU in an Era of Insecurity?

‘Europe is in danger.’[1] This is the consensus arrived at by High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice President of the European Commission (HR/VP) Josep Borrell and European Defence Ministers at a meeting of the European Council on 15 November 2021.[2] The EU and its Member States are caught in a rapidly evolving security environment. The geostrategic picture has become fluid and competing spheres of influence are disrupting the multilateral system.[3]

In response to this shifting landscape, the European Council has proposed the development of a Strategic Compass. Set to be released in March 2022, the Compass will set out an ‘assessment of the threats and challenges’ the EU faces and will ‘propose operational guidelines’ to enable the EU to become ‘a security provider for its citizens.’[4] Having been conceived by the European Council, the Strategic Compass is an attempt to set the strategic vision of the Union from the top-down, while simultaneously building consensus among Member States from the bottom-up, by drawing upon their diverse perspectives to provide an instrument for coordinating their foreign policies.

A Shared Threat Analysis for a new Era of Insecurity

The Strategic Compass rests on a common threat analysis produced using the SIAC (Single Intelligence Analysis Capacity) at the European Intelligence and Situation Centre (INTCEN). This is part of the crisis management structures of the European External Action Service – the EU’s diplomatic arm[5]. This ‘comprehensive 360 degrees analysis’ of the range of conventional and hybrid threats the EU is facing is the first review of its kind undertaken by the EU[6]. Ultimately, this analysis seeks to provide a ‘common understanding’ of the threats and challenges which Member States face.[7]

This shared threat analysis categorises these challenges under three strands.[8]

- Global: The slowdown of globalisation, growing economic rivalry between global powers, climate change and competition for resources alongside the hollowing out of the multilateral system threaten the EU and its Member States.

- Regional: Instability, conflict, state fragility, inter-state tensions, and the destabilising impact of non-state actors increasingly threaten peace on a regional level.

- Threats Against the EU: the SIAC believes that the EU being targeted by state and non-state actors, the mobilisation of hybrid tools such as disinformation and the instrumentalization of migration, and the ongoing risk of terrorist activity and attacks collectively represent a direct threat to European security.

What is the Point? The Utility of the Compass in a Landscape of Insecurity

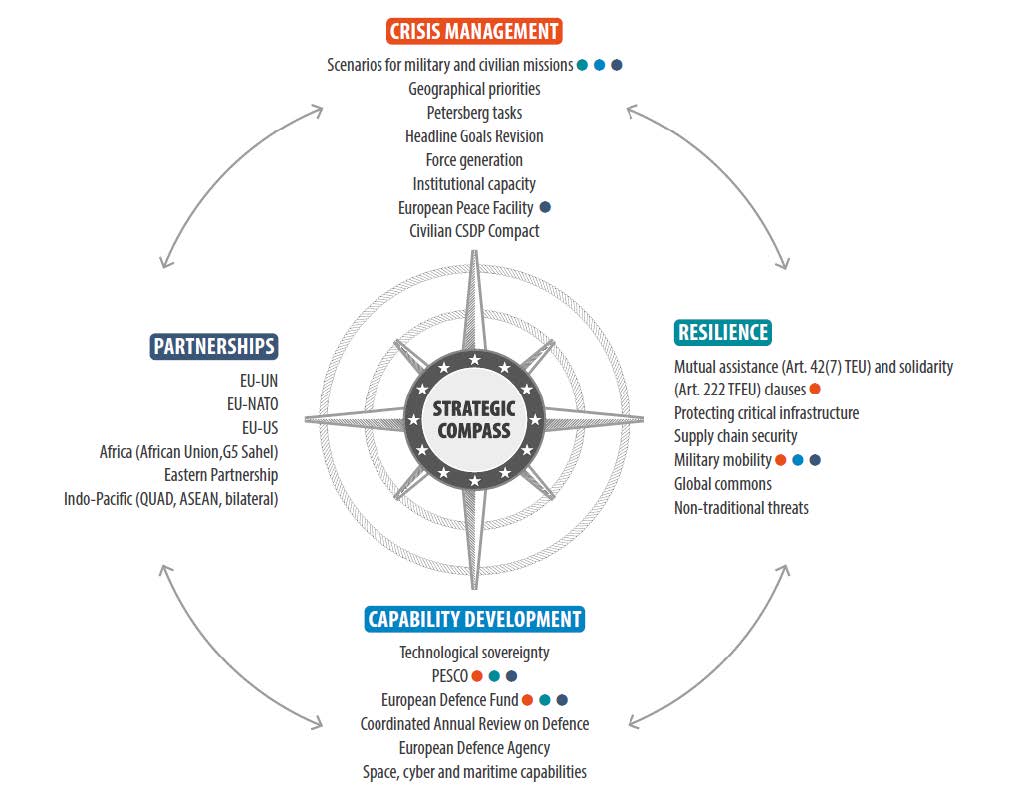

In a multidimensional risk landscape that is increasingly characterised by both conventional and novel threats,[9] no individual EU Member State ‘has the strength nor the resources to address these threats alone.’[10] In this regard, the Strategic Compass will inform future EU policies and strategies across four work strands, namely: (1) Act; (2) Secure; (3) Invest and (4) Partner.[11]

(1) Act

In his foreword to the Strategic Compass, HR/VP Borrell has asserted that ‘we need an EU which is able to act rapidly and robustly whenever a crisis erupts with partners if possible and alone when necessary.’[12] The Strategic Compass aspires to improve the effectiveness of the EU’s operational engagement by mobilising civilian experts, military forces and the full use of the European Peace Facility – a mechanism which will fund the common cost of Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions until 2027.

The proposal for the development of an EU Rapid Deployment Capacity (EURDC) is amongst the most ambitious elements of the Strategic Compass. It will enable the EU to deploy a modular force of 5000 troops[13] capable of completing full spectrum-operations in land, air and maritime theatres. Though clarity is lacking as to the final form that the EURDC will take, in a discussion with the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Director General of the EU Military Staff (EUMS) Vice-Admiral Hervé Bléjean, indicated that the EURDC will likely be a reformulation of the EU Battlegroup capability.[14] Yet, despite their use being contemplated in Libya (2011) and Mali (2012), the EU Battlegroups have never been deployed, due to a perceived ‘dwindling appetite to activate the hard edge of CSDP.’[15] However, a lack of willingness to exercise ‘hard’ capabilities is a well-known issue impinging on the EU’s ability to be an effective global actor when it comes to security matters. Both Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and HR/VP Josep Borrell argue that the EU needs to step up its ‘willingness[16] and that a ‘lack of political will’ to use its forces has impeded the EU in becoming a real security provider.[17] This casts doubt over the EU’s dispensation towards action when reacting to rapidly unfolding crises that require full-spectrum responses such as another ‘Kabul Airport moment’, following theUS withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021.[18]

Strategic Compass process and its baskets

(2) Secure

HR/VP Borrell argues that the EU needs to enhance its ability to anticipate threats, guarantee secure access to strategic domains such as space and cyber, and to protect its citizens.[19] As part of the Strategic Compass initiative, the EU Intelligence Centre (INTCEN) will acquire an enhanced role as a single-entry point for Member States’ intelligence and security services[20] for shared intelligence data. Synchronising the EU’s intelligence capabilities in the form of the shared threat analysis facility as a part of the SIAC has already highlighted the need to improve the Union’s resilience when it comes to matters of security. Resilience, as the ability to ‘renew, resist’ and to be ’crisis-proof’ when faced with internal and external threats’[21] is a central element of the EU’s overarching Global Strategy for Foreign and Security Policy.[22] The current geostrategic climate has seen the space, cyber and maritime domains becoming increasingly contested[23] and the EU will need to develop new strategies and capacities to enhance its resilience in these strategic domains. A Space Strategy for Security and Defence has been proposed by HR/VP Borrell to secure a level playing field in this arena and unhindered EU access to space. Simultaneously, the Compass will recommend that the Coordinated Maritime Presences tool should be enhanced and expanded with new areas of maritime interest being considered. Finally, the Compass will include a recommendation for the creation of a ’hybrid toolbox’ including measures to be taken against non-conventional security threats such as cyber-attacks.[24]

(3) Invest

HR/VP Borrell, as well as other EU leaders, have highlighted the need for the EU to be more ambitious and coordinated in both supporting the European Defence industry and correspondingly in maintaining the Union’s competitive edge in military and technological capabilities.[25] This will necessitate a strengthening of the EU’s Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB) - the sum of the European industries who supply and equip Europe’s militaries. The European Defence industry has traditionally been at the edge of research and development (R&D)[26] and is a key component underpinning Europe’s autonomy.[27] Yet, defence R&D strategies are long-term policies which necessitate decades of development and funding. Existing European military R&D capacity is the result of decisions taken decades ago.[28] The reality that the EU’s Defence Industry is highly fragmented[29] with an estimated €26.4 billion a year being wasted due to duplication and overcapacity,[30] continues to blunt the Union’s military edge. In a bid to sharpen it, the EU has approved the European Defence Fund (EDF), a mechanism providing a budget of around €8 billion until 2027 to fund ‘collaborative capability development projects.’[31] By facilitating joint purchasing and development, the defragmentation of defence spending under the EDF and the Strategic Compass allows Member States to benefit from economies of scale in their procurement procedures, thereby enabling EU militaries to obtain more capabilities for less money.

(4) Partner

The final point of the Compass focuses on strengthening partnerships with multilateral organisations and third countries who share common values and interests[32] across a variety of domains and geographic areas. With multilateralism and the rules-based order having already been under threat before the pandemic[33] from actors such as Russia, China and Iran seeking to tilt the international order in their favour,[34] the Strategic Compass asserts the EU’s commitment to teaming up with like-minded partner organisations and countries to defend the rules-based order founded on international law and multilateral treaties.[35] Notably, with a new Joint-Declaration expected in March 2022, the Strategic Compass will highlight the importance of the EU’s continued cooperation with NATO. Moreover, the EU will enhance its cooperation with other multilateral organisations such as the OSCE and ASEAN, alongside individual partners such as the US and the UK.

The Strategic Compass: A Pathway to Overcome the Inertia of Passivity

The EU now finds itself in a new age of insecurity and can no longer enjoy the comfort and safety to which many in the West had grown accustomed in the era of monopolarity following the fall of the Soviet Union. While it was fairly argued at the beginning of the 21st century that ‘people fortunate enough to live in Western societies’ were probably ‘more secure than at any point in the twentieth century,’[36] the return of geostrategic competition; the rise, fall and resurgence of the Islamic State group and the COVID-19 Pandemic among much else means that we can no longer feel such confidence in our collective security. Indeed, the developing situation on the EU’s eastern fringes and an increasingly assertive Russia has caused some to conclude that the post-Cold War chapter has drawn to a close, and a new chapter has opened, bringing with it new strategic challenges and threats.[37]

To remain relevant and to protect the security and interests of the European citizenry, the EU must be able to respond rapidly, efficiently, and effectively to crises as they develop. The development process of the Strategic Compass is an important step towards enhancing the EU’s crisis response capacity and focuses on creating a modular instrument for Member States to enable them to respond both collectively and individually to security threats. The introduction of the Strategic Compass has the potential to be a watershed moment for the EU, enabling the bloc to protect its interests and defend its citizens in an epoch of increasing uncertainty. However, this will only be possible if the Compass is backed-up by the necessary political will and a willingness to act. Should these critical components be neglected, the EU’s Strategic Compass may end up being little better than a paper weight.

[1] Borrell 2021: Time to Move Forward with the Strategic Compass 18 November 2021. EEAS. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/regions/middle-east-north-africa-mena/107464/time-move-forward-strategic-compass_en

[2] Borrell 2021: Memo: Questions and Answers: A Background for the Strategic Compass. EEAS. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-09-12_-_memo_-_strategic_compass_-_final.pdf

[3] Anghel, Lazarou, Saulnier, Wilson 2020 Pp.8/9 On the Path to ‘Strategic Autonomy’: The EU in an Evolving Geopolitical Environment. EPRS. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/652096/EPRS_STU(2020)652096_EN.pdf

[4] Borrell 2021: Memo: Questions and Answers: A Background for the Strategic Compass. EEAS. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-09-12_-_memo_-_strategic_compass_-_final.pdf

[5] EEAS 2021: Memo: Questions and Answers: Threat Analysis – a background for the Strategic Compass. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2020_11_20_memo_questions_and_answers_-_threat_analsysis_-_copy.pdf

[6] Ibid

[7] Borrell 2021: Memo: Questions and Answers: A Background for the Strategic Compass. EEAS. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-09-12_-_memo_-_strategic_compass_-_final.pdf

[8] EEAS 2021: Towards a Strategic Compass for the EU. EEAS. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/towards_a_strategic_compass-2021-11.pdf

[9] Anghel, Lazarou, Saulnier, Wilson 2020: p37 On the Path to ‘Strategic Autonomy’: The EU in an Evolving Geopolitical Environment. EPRS. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/652096/EPRS_STU(2020)652096_EN.pdf

[10] Mogherini 2016: Foreword to the EU Global Strategy. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/statements-eeas/docs/foreword_hrvp_en.pdf

[11] Borrell 15 November 2021

[12] Borrell 2021: Memo: Questions and Answers: A Background for the Strategic Compass. EEAS. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-09-12_-_memo_-_strategic_compass_-_final.pdf

[13] Ibid

[14] CSIS 2021: The EU’s New Strategic Compass. CSIS. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=thJEXAUWCKc

[15] Barcikowska 2013: 4. EU Battlegroups – Ready to go? EUISS. Available at:

[16] Borrell 2021: Memo: Questions and Answers: A Background for the Strategic Compass. EEAS. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-09-12_-_memo_-_strategic_compass_-_final.pdf

[17] von der Leyen 2021. European Union State of the Union 2021. Available at: http://www.iss.europa.eu/uploads/media/Brief_40_EU_Battlegroups.pdf https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_21_4701

[18] Latici and Lazarou 2021: p4: Where will the Strategic Compass Point? EPRS. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/698057/EPRS_BRI(2021)698057_EN.pdf

[19] Borrell 2021: Memo: Questions and Answers: A Background for the Strategic Compass. EEAS. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-09-12_-_memo_-_strategic_compass_-_final.pdf

[20] Ibid

[21] Bendiek, 2017: 6. A Paradigm Shift in the EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy: From Transformation to Resilience, SWP. Available at: https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/research_papers/2017RP11_bdk.pdf

[22] Anghel, Lazarou, Saulnier, Wilson 2020: p47 On the Path to ‘Strategic Autonomy’: The EU in an Evolving Geopolitical Environment. EPRS. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/652096/EPRS_STU(2020)652096_EN.pdf

[23] Borrell 2021: Memo: Questions and Answers: A Background for the Strategic Compass. EEAS. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-09-12_-_memo_-_strategic_compass_-_final.pdf

[24] Ibid

[25] Borrell 2021: A Strategic Compass to Make Europe a Security Provider. EEAS. Available at: foreword_-_a_strategic_compass_to_make_europe_a_security_provider.pdf (europa.eu). See also: von der Leyen 2021: State of the Union Address. Available at: State of the Union Address by President von der Leyen (europa.eu)

[26] Anghel, Lazarou, Saulnier, Wilson 2020: p40 On the Path to ‘Strategic Autonomy’: The EU in an Evolving Geopolitical Environment. EPRS. Available at:

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/652096/EPRS_STU(2020)652096_EN.pdf

[27] Anghel, Lazarou, Saulnier, Wilson 2020: p29 On the Path to ‘Strategic Autonomy’: The EU in an Evolving Geopolitical Environment. EPRS. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/652096/EPRS_STU(2020)652096_EN.pdf

[28] Anghel, Lazarou, Saulnier, Wilson 2020: p40 On the Path to ‘Strategic Autonomy’: The EU in an Evolving Geopolitical Environment. EPRS. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/652096/EPRS_STU(2020)652096_EN.pdf

[29] Mogherini 2016: p21 EU Global Strategy on Foreign and Security Policy: Implementation Plan on Security and Defence. EEAS. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eugs_implementation_plan_st14392.en16_0.pdf

[30] Europarl 2021 Is the EU Creating a European Army. European Parliament. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/security/20190612STO54310/eu-army-myth-what-is-europe-really-doing-to-boost-defence

[31] European Commission 2021 The European Defence Fund. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/defence-industry-space/eu-defence-industry/european-defence-fund-edf_en

[32] Borrell 2021: Memo: Questions and Answers: A Background for the Strategic Compass. EEAS. Available at: https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-09-12_-_memo_-_strategic_compass_-_final.pdf

[33] Anghel, Lazarou, Saulnier, Wilson 2020: p28 On the Path to ‘Strategic Autonomy’: The EU in an Evolving Geopolitical Environment. EPRS. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/652096/EPRS_STU(2020)652096_EN.pdf

[34] Mazzar 2015: 1 Mastering the Gray Zone: Understanding A Changing Era of Conflict. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College

[35] Anghel, Lazarou, Saulnier, Wilson 2020: p30. On the Path to ‘Strategic Autonomy’: The EU in an Evolving Geopolitical Environment. EPRS. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/652096/EPRS_STU(2020)652096_EN.pdf

[36] Vedby Rasmussen 2009: 1. The Risk Society at War: Terror, Technology and Strategy in the Twenty-First Century. University of Cambridge Press.

[37] Walshe 31 January 2022: Europe Must Shed Its Illusions About Russia. Foreign Policy. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/31/europe-russia-putin-ukraine-germany-france-nato-uk-illusions/