Pledges, “ratchet” mechanisms and clean-tech innovation: The three pillars of a successful Paris outcome

A new approach to fostering international cooperation on climate action will be road tested at the Paris climate conference. At its heart are pledges made by individual countries to manage their carbon footprints. So far 180 countries have come forward with commitments covering over 95% of global emissions.

Focusing on national pledges can be traced back to the Copenhagen conference in 2009, when the international community failed to agree a climate treaty binding all countries. The lesson was clear. Attempting to impose legally binding targets on countries from above – an approach then favoured by the EU – would be resisted, particularly by emerging economies such as China and India.

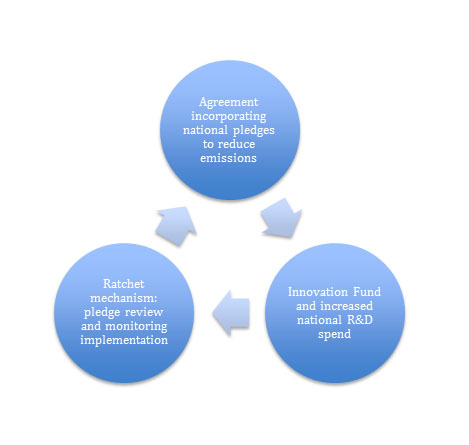

A successful outcome in Paris1 would build on the following three pillars (Fig 1):

- Tying national pledges into a comprehensive international agreement;

- Agreeing a “ratchet” mechanism to compare, monitor implementation and increase the ambition of pledges over time.

- Oiling the ratchet mechanism by boosting clean-tech R&D, thereby ensuring more cost-effective solutions are available over time.

Fig 1. Three Paris pillars to increase ambition over time

Delivering in these three areas could help address the elephant in the Paris room: the lack of collective ambition, which leaves the world on course for severe, irreversible and potentially catastrophic climate change.

The first objective of negotiators will be to incorporate national pledges into an agreement or Treaty of some sort. The legal nature of the agreement and its constituent parts will receive quite a bit of attention. But perhaps this risks missing the point. Kyoto was a legally binding treaty, but its legal standing did nothing to ensure US ratification, or to prevent Canada withdrawing when it became clear that its targets would not be met.

If Copenhagen was a train with no one aboard, Paris is a train moving too slowly. Assessments of the aggregate impact of pledges currently on the table suggest that planetary warming could reach approximately 2.7 degrees Celsius by 2100. While this is less than the current trajectory of 4 degrees or more, the pledges are clearly insufficient to meet the globally agreed target 2 degree target. Managing the trade off between inclusivity and ambition is perhaps the key challenge facing negotiators.

So how can we speed the Paris train up over time? The key is the “ratchet mechanism”, aimed at monitoring implementation of pledges and allowing for increased ambition every five years. The scope of the ratchet mechanism is unclear. Would the ratchet mechanism concern itself with what countries ought to contribute, considering their “common but differentiated” national circumstances? If so what yardsticks would be used to assess commitments – emissions per capita, historic responsibility for climate, emissions per unit GDP, availability of cost-effective mitigation potential? To what extent will the review process involve peers or international actors, or would it be nationally led? Making ambitious pledges is one thing, delivery is another, with climate “implementation gaps” evident in many OECD countries. Would a ratchet mechanism monitor implementation of pledges, or would that be left to a separate mechanism? A third option – clearly less desirable from an environmental perspective - would leaving countries to their own national devices, or a national review process.

Another difficulty to be grappled with is comparability of pledges, which is a necessary condition for transparent review. The Lima negotiations had tried to agree a template for pledges in December 2014. The agreement stated that pledges should be developed in a manner “that facilitates …clarity, transparency and understanding”, and that they “may” include several elements (timeframes, scope, assumptions etc.) that would enable comparability. The weakness of the Lima outcome is evident in the pledges that have been submitted. Compare, for example, Saudi Arabia’s pledge, which contains no commitment of any sort, with the EU pledge. The latter details a clear target for emissions reduction, a baseline, and an explanation of why the EU considers its pledge “fair and ambitious”. Can countries be persuaded to follow a template when making pledges? As this seems unlikely, reviewers may be faced with comparing bananas with tomatoes.

The third ingredient, more clean-tech R&D spend, is necessary to lubricate the ratchet mechanism, and facilitate emerging economies in taking on more ambitious pledges every five years. While major strides have been made in making on-shore wind cost-effective, more innovation is required in “enabling technologies” to reduce the variability of wind and solar PV or increase the flexibility of power systems. Key areas include demand-side integration, energy storage and smart grid infrastructure. Other technologies on the generation side such as carbon capture and storage have made almost no progress over the past decade. Paris has perhaps already exceeded expectations on this respect, following the announcement of two separate initiatives on the first day. “Mission Innovation” is a Government initiative involving 20 countries,including the US, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, India, Japan and China. Its objective is to double the level of clean tech innovation over the next five years.

A separate though related private-sector initiative led by Bill Gates, the Breakthrough Energy Coalition, seeks to mobilise investment from 28 billionaires in a way that will be “truly transformative”. Its objective is to “focus on early stage companies that have the potential of an energy future that produces near zero carbon emissions and provides everyone with affordable, reliable energy”. It will be interesting to watch the development of these two initiatives, how they are coordinated and what value added they bring.The focus on more R&D is welcome. It shouldn’t be forgotten, however, that in many cases what is required is the deployment of already mature and cost-effective technologies. There needs to be a focus on removing non-economic barriers preventing deployment and an understanding that low-carbon transition is a societal project involving people, communities, and institutions, not just technologies. Nor does the urgency of the challenge permit the luxury of waiting for silver bullet solutions that may never arrive.

To conclude, a new approach to international negotiations will be tested in Paris. Facilitating countries in determining their own pace and levels of commitment has succeeded in brining all major players to the table. Now the key is to ensure more ambitions national pledges. Three pillars for a successful outcome from negotiations are therefore emerging. The first is national pledges, preferably following an agreed template and incorporated into an international agreement. Second a robust, transparent and effective “ratchet” mechanism to review pledge ambition and implementation. And finally the magical ingredient is more funding for clean-tech R&D, which can lubricate the ratchet mechanism and speed up global decarbonisation over time.

These are the yardsticks by which I’ll be judging the Paris outcome.

Joseph Curtin is Senior Fellow for climate policy at IIEA and UCC, and a member of Ireland’s recently established national Climate Change Advisory Council.

1 I set aside important negotiations on finance and adaptation to focus on mitigation in this analysis