How will Brexit impact Irish Freight Movements?

Author: Tom Ferris

Tom Ferris is a life member of the Institute of International and European Affairs. He was formerly the Department of Transport’s Senior Economist.

Introduction

As an island economy, Ireland is highly dependent on transport. Trading as it does in the global marketplace, freight movements form a large part of the transport sector. This blog looks at some of the implications for Ireland’s freight movements after the post-Brexit United Kingdom ends its present ‘transitional’ relationship with the EU. The extent of the impact will depend on whether (or not) the Withdrawal Agreement[i] and the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland[ii] are fully implemented at the end of the current transition period. The transition period is due to end on 31 December 2020. That can be extended by up to one to two years. But such a decision must be taken jointly by the EU and United Kingdom before 1 July 2020.

Overall Freight Sector

Ireland is the only EU Member State with a land-border with the UK. Accordingly, the movement of goods to and from the UK, including goods transiting the UK, will be affected once the present transitional arrangements end. And the volumes of cargo going to and from the UK through Irish ports are considerable. CSO data show that traffic going to and from UK ports amounted to 21 million tonnes in 2019. This represents nearly 40 per cent of the overall total cargo of 53 million tonnes that traversed Irish Ports in 2019.[iii]

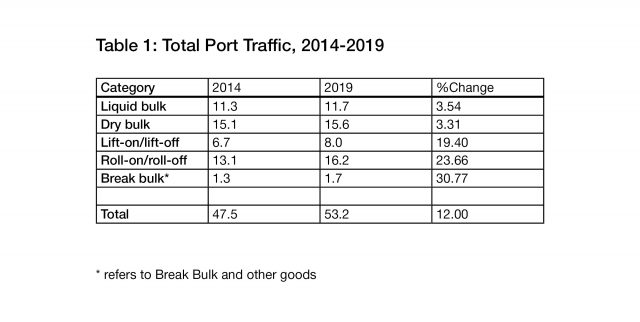

The overall total cargo of 53 million tonnes is made-up of five categories of traffic. This blog focuses on only two categories, namely Roll-on-Roll-off (RoRo) traffic and Lift-on-Lift-off (LoLo) traffic; these two categories are usually referred to as ‘Containerised Traffic’. The other three segments of total traffic, which are not embraced by this blog, are Liquid Bulk; Dry Bulk; and Break Bulk. Table 1 captures all five categories and show their performance between 2014 and 2019. Each component grew, but at different rates, over the five year period. Break bulk grew at the fastest rate, by over 30%; while liquid bulk and dry bulk both grew at rates of less than 4%. RoRo grew by nearly 24% and LoLo by nearly 20%.

RoRo and LoLo Traffic

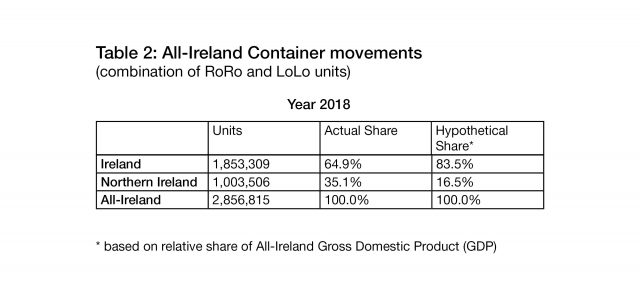

The foregoing table shows the volumes of RoRo and LoLo traffic directly traversing Irish ports. As well as these volumes, some additional cargo moves by air[iv] and some through ports in Northern Ireland. While detailed statistics are not available on cross-border trade, it is possible to calculate the flows by combining official container data for Northern Ireland with container data for the Republic of Ireland. The data are provided by the Central Statistics Office (for Republic of Ireland) and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (for Northern Ireland Ports). The measure used for this comparative work is the number of ‘container units’ rather than ‘tonnage’. The numbers of containers measured are a combination of RoRo units and LoLo units for the year 2018. Table 2 shows that over 35.1% of all container movements (2.9 million) went through Northern Ireland ports in 2018, while Northern Ireland’s share of All-Ireland GDP was estimated at 16.5 percent. This is over twice the proportion that would be expected, using Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a proxy measurement.

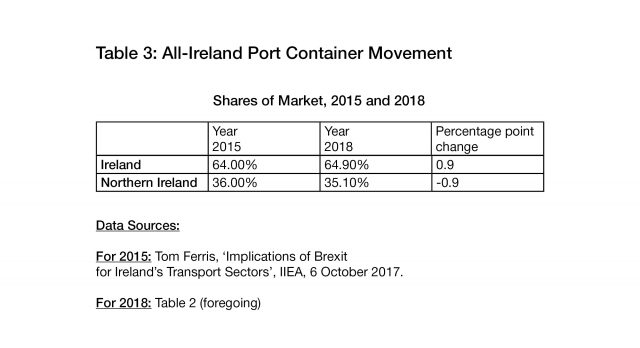

A question arises as to whether there has been a change in market shares for container movements since the result of the June 2016 UK Referendum signalled the prospect of the introduction of border procedures? The evidence shows, somewhat surprisingly, that there has been only a marginal change. An IIEA paper from 2017 had shown that 36% of all container movements went through Northern Ireland ports in 2015.[v] This is a reduction of less than 1 percentage point in the three year between the years 2015 and 2018. It might well be that more recent data, for 2019 and 2020, will show more significant changes in market shares. Table 3 shows the data for 2015 and 2018.

Landbridge

The UK Landbridge refers to the routes that some Irish freight uses to move to and from mainland Europe via UK roads and ports. At present, Irish importers and exporters use the landbridge to transport high value or time sensitive goods, because it offers significantly faster transit times than alternative routes.[vi] The Irish Maritime Development Office (IMDO) produced a very useful study on the important role that landbridge plays in Irish freight transport. The study points out that – “Although the landbridge option is more expensive than direct routes when UK haulage costs are included, its superior transit time is a competitive prerequisite in certain industry sectors”. It also highlighted the extent to which the landbridge route offers superior transit times to European markets: “The alternative is to use direct Roll-on / Roll-of (RoRo) or Lift-on / Lift-of (LoLo) services to the continent, both of which add significantly to transit times. The landbridge route through Dublin and Calais takes approximately 20 hours, when time in port is included. Comparable direct RoRo services can take up to 40 hours and direct LoLo services can take up to 60 hours”.[vii]

How significant is the landbridge? The IMDO used CSO trade figures and port traffic statistics to measure the scale of landbridge traffics. It concluded that - “...the volume of RoRo traffic using the Landbridge to transport goods to and from European ports is approximately 3,000,000 tonnes, which equates to around 150,000 Heavy Goods Vehicles (approximately 16% of the RoRo traffic between Ireland and Britain)”. This shows that the landbridge is an important route to market for many Irish importers and exporters. The introduction of border procedures between the UK and Ireland and between the UK and the continent will impact negatively on the efficiency and speed of land bridge routes. And procedures can take many forms, ranging from tariffs, customs controls (and delays) to the application of different vehicle standards and road charging.

Impact of Brexit

Brexit will certainly impact on the Irish Freight sector. The impact will be felt least if the Withdrawal Agreement is fully implemented. However, the scope for minimising impacts is limited. Landbridge traffics do have a choice; they can switch to direct sea routes to mainland Europe, although transit times are much longer. Already shipping companies have been increasing capacity for direct sea services, up to being able to respond to a ‘No Deal’ scenario in the negotiations over the future relationship. In reply to a Dail Question, Transport Minister, Shane Ross, stated last September that – “...I believe that sufficient capacity should be available on direct routes to continental ports following a ‘No Deal’ Brexit and should demand for further capacity arise, because of disruption to the UK landbridge, the shipping sector have assured my Department and the IMDO that they can and will respond quickly to meet such demands.” [viii] [ix]

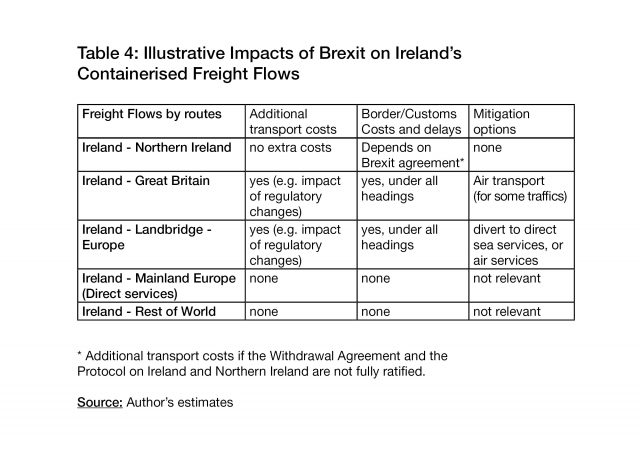

Other flows of traffic do not have choices. And they will be affected adversely in different ways. Table 4 has been constructed for this blog to illustrate some of the possible impacts.

It should be noted that the scale of costs, for Irish exports and imports, depend on whether the introduction of borders are accompanied by regulatory divergences between the EU and the UK. Estimates of such costs have been calculated by Copenhagen Economics in its Brexit Report, which was published in 2018 for the Irish Government. It calculated that – “If no regulatory divergence occurs between the EU and the UK, Irish goods exports will face additional trade costs related to tariffs and customs procedures corresponding to an average 4-5 per cent trade cost in the EEA, CU and FTA scenarios and around 7-8 per cent additional trade cost in the WTO-scenario. If regulatory divergence occurs in the long run up to the maximum estimates described above, trade costs for Irish goods to the UK may increase by 12 to 32 per cent”.[x][xi]

Some conclusions

In the short term, the Irish freight market will be relatively unaffected, if the transition period under the Withdrawal Agreement is in fact extended by up to two years. For this to happen, however, a decision must be taken jointly by the EU and United Kingdom before 1 July 2020. There is no great optimism that this will happen. If it doesn’t happen, then there are two main scenarios. First, the full ratification of the Withdrawal Agreement and the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland. That scenario will have the least negative impact on the Irish freight sector; but there will be negative impacts. Second, the ‘No Deal’ scenario; the adverse effects will be much greater under this scenario if it materialises. In particular, border and customs controls are likely to be re-imposed between the UK and the EU Member States. Moreover, there is the likelihood of an increase in transaction costs and the imposition of restrictions on the free movement of goods of goods entering and leaving the UK. These will add to overall costs and transit times for freight transport. Such costs will feed into the overall cost of products, both imports and exports. In turn, they will impact negatively on the competitiveness of Irish businesses in the future.

[i] The EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement , 12 November 2019 https://ec.europa.eu/info/european-union-and-united-kingdom-forging-new-partnership/eu-uk-withdrawal-agreement_en

[ii] Revised Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland, 17 October 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/publications/revised-protocol-ireland-and-northern-ireland-included-withdrawal-agreement_en

[iii] Central Statistics Office, ‘Port Statistics 2019, 27 May 2020 https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/spt/statisticsofporttrafficquarter4andyear2019/

[iv] Air cargo represents less than one percent of overall freight movements, by weight, to and from Great Britain. Such cargo tends to be made-up of high-value, lightweight, commodities.

[v] Tom Ferris, ‘Implications of Brexit for Ireland’s Transport Sectors’, IIEA, 6 October 2017, https://www.iiea.com/publication/implications-of-brexit-for-irelands-transport-sectors/

[vi] The shorter transit times are particularly important for perishable goods; competitive supply chains and high value goods.

[vii] Irish Maritime Development Office, ‘Implications of Brexit on the use of the Landbridge’, 2018 https://www.imdo.ie/Home/sites/default/files/IMDOFiles/A143219%20IMDO%20Landbridge%20Report-digital-draft1.pdf

[viii] Reply to Dail Question by Minister Shane Ross, T.D., 24 September 2019 https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2019-09-24/444/?highlight%5B0%5D=freight&highlight%5B1%5D=brexit&highlight%5B2%5D=transport

[ix] It should be noted that the current disruption caused by Covid-19 has necessitated the emergency provision of a maximum contribution of €15 million from the Irish Government towards the costs involved in the continued operation of RoRo freight and passenger ferry services on five strategic maritime routes into and out of Ireland over a three month period. The operators currently providing these services are Irish Ferries, Stena Line and Brittany Ferries.

[x] These abbreviations refer to the European Economic Area (EEA) scenario; the Customs Union (CU) scenario; the Free trade agreement (FTA) scenario and World Trade Organisation scenario (WTO)

[x] Copenhagen Economics, ‘Ireland & Impacts of Brexit Strategic Implications for Ireland arising from Changing EU-UK Trading Relations’, February 2018, https://www.copenhageneconomics.com/publications/publication/ireland-the-impacts-of-brexit