From Dependence to Interdependence: Reflections on Ireland’s EU Accession Journey

From Dependence to Interdependence

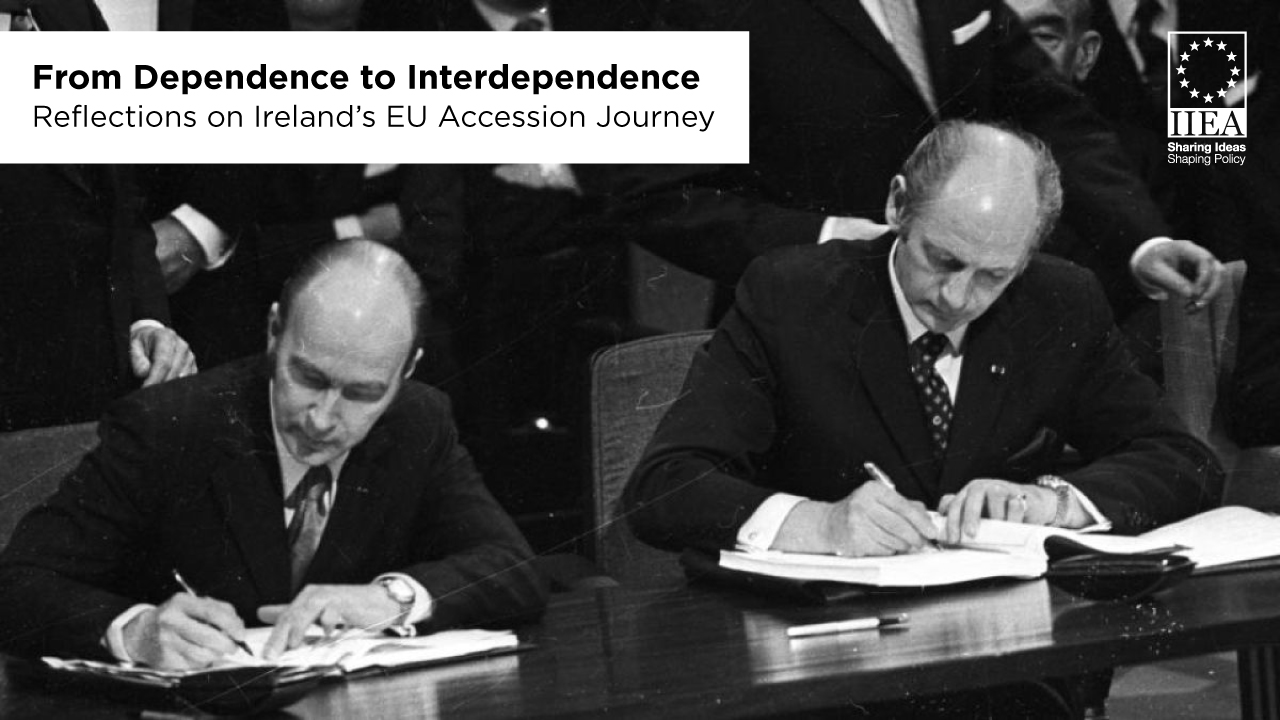

The 22nd of January 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of Ireland’s signature of the Act of Accession to the European Economic Community (now the European Union), this blog will assess the importance of this historic step into Europe and map Ireland’s journey from the edges of Europe to the heart of the EU, and what it meant for both Ireland and Europe.

The Prelude

The initial phases of European integration effectively bypassed Ireland, as the initial “Schuman Declaration”[1] focused on rebuilding European economies and societies after the Second World War during the 1950s, while Ireland, which had been neutral during the war, followed a more isolated protectionist economic model based on self-sufficiency. The 1959 Fianna Fáil Government of Seán Lemass set Irish membership of the European Economic Community (EEC) as a key objective and planned to position Ireland at the heart of European economic and political developments.[2] During the 1960s Ireland’s economic strategy was to open its economy gradually to increased levels of foreign trade and competition with the UK and other markets.

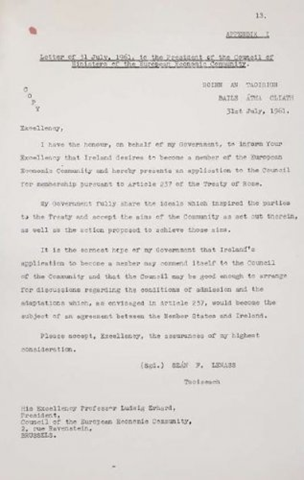

Initial letter of application – 1961 from Taoiseach Seán Lemass

In a 1970 White Paper on European Membership drafted by the Irish Government,[3] it was determined that EEC membership would enable Ireland to play a considerable role in shaping the political development of the Community and that despite initial concerns over the competitiveness of Irish industries in the Common Market, long-term membership would be economically beneficial. Ireland’s critical agricultural sector was a prime concern during negotiations and the White Paper emphasised that EEC membership would also greatly benefit agricultural producers, particularly livestock farmers.

Contemporary Dáil debates on membership also recorded the enormous potential that access to a wider European market would have on the Irish economy and on reducing Ireland’s economic dependency on the UK.[4][5]

The implementation of the principle of equal-pay between men and women and the abolition of marriage-differentiated scales and the marriage bar would signal a seismic shift in Irish society; and would open up avenues of economic and professional advancement for women.

As a poor country on the periphery of Europe, Ireland would benefit from Community membership: access to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and regional Cohesion Funding programmes would enable Ireland to support farmers, open new markets, invest in improved public infrastructure, and attract inward investment. The initial discussions focused on the “serious economic and social imbalances of a regional and structural nature” faced by Ireland and stressed the need for tax-breaks for exporters to support underdeveloped areas. This commitment to reducing gaps in income and living-standards across the Community was incorporated into a special annex of Ireland’s Act of Accession.[6]

The Irish application for membership was not uniformly welcomed by the Community of “Six”. Due to Ireland’s relative economic underdevelopment, policy of neutrality and non-membership of NATO its potential accession was viewed with suspicion by the Six, but the transformative impact of Taoiseach Seán Lemass’ personal diplomatic overtures and Minister for Foreign Affairs Patrick Hillery’s skilful negotiating tactics ultimately succeeded in overturning these concerns.

Third Time Lucky: The Journey to Membership

Ireland’s application to join the European Economic Community was a journey from dependence to interdependence, as Ireland’s political and economic fortunes were inextricably connected those of the UK, given the close economic interlinkages between the two, and Ireland’s economic dependence on the British export market, which accounted for approximately 75% of all exports (mainly agricultural products).

The UK’s first application to join the EEC was submitted in August 1961, swiftly followed by Ireland in October 1961, but was thwarted over British concerns about how membership of the Common Market would impact the UK’s preferential trade agreements with the Commonwealth and by French concerns about liberalisation of agricultural production.

In January 1963, French President Charles de Gaulle effectively vetoed UK accession, and by extension Ireland's own application in a press conference, citing Britain’s overly close ties to the US and distinct trade relationship with its former empire.[7] This unilateral decision by France was met with strong opposition from the other Five members of the Community who felt that they had not been sufficiently consulted. In an emotional speech, then-Lord Privy Seal and later British Prime Minister, Edward Heath, on 29 January 1963 assured the Community that, “We in Britain are not going to turn our backs on the mainland of Europe or the countries of the Community. We are a part of Europe: by geography, tradition, history, culture and civilisation. We shall continue to work with all our friends in Europe for the true unity and strength of this continent.”[8] Ireland withdrew its application following the rejection of the UK in order to maintain its crucial economic links with the British market.

De Gaulle press conference where he refused UK (and Ireland) accession – January 1963

Ireland’s second foray into EEC membership in May 1967 alongside the UK involved two further candidates, Norway and Denmark. And once again the UK were rejected by President de Gaulle’s “velvet veto” stating that the conditions weren’t right for British entry. Despite Taoiseach Jack Lynch’s considerable diplomatic efforts to keep accession on the table, the Six decided not to go forward with any applications. However, de Gaulle’s resignation in 1969 and replacement by President Pompidou offered the realistic prospect of membership.

Conference room at the Hague Summit (1 and 2 December 1969)

In December 1969, at a summit in The Hague, EEC leaders set out the terms for joining the “Six”, whereby candidate countries would negotiate with the Community as a whole represented by the Commission. This prevented individual members undermining negotiations or candidates splitting the Community. The leaders also decided during the summit that candidates must accept the treaties and decisions made by the Community since 1958 in their entirety, removing the opportunity for cherry-picking.[9 ]

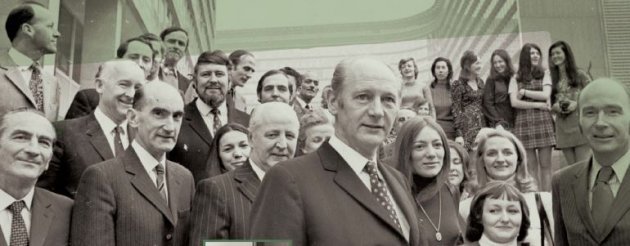

Taoiseach Jack Lynch (centre), Minister for Foreign Affairs Patrick Hillery (far right) at the Irish negotiating and accession team in Brussels, 1972.

Formal negotiations finally began in mid-1971 between Ireland, Denmark, Norway and the UK and the Community with the goal of EEC membership now firmly in sight.

A New Era

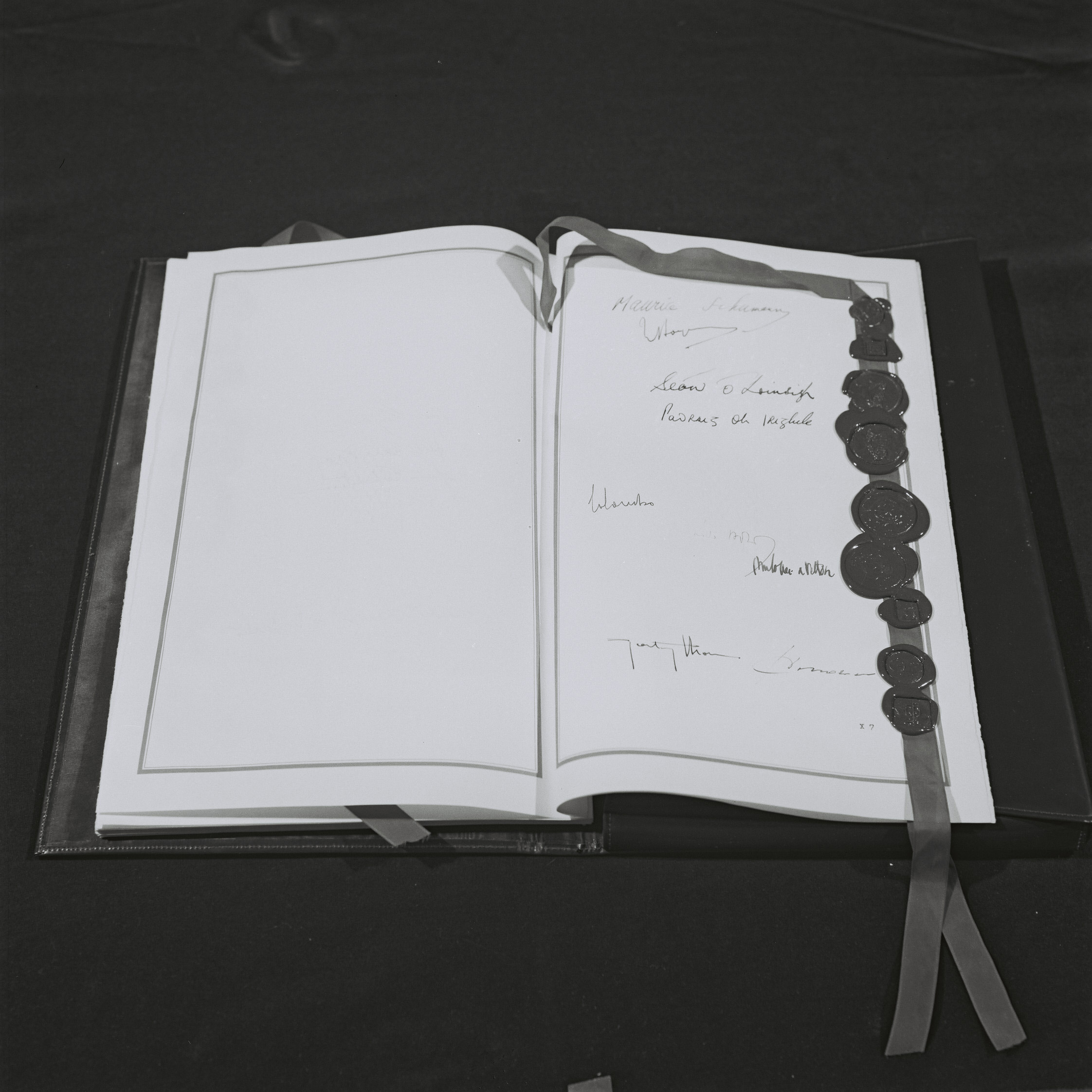

Ireland’s entry into the EEC alongside the UK and Denmark, following successful respective accession referenda, not only had consequences for Ireland, but also changed the nature of the Community itself as it grew from a predominantly economic organisation into a social and political community. On 14 December 1973, the leaders of the “Nine” met in Copenhagen and published a “Declaration on European Identity”, a common statement on their values and identity. This combination of a democratic club founded on liberal values of pluralism and a shared culture backed by national political leaders, like West German Chancellor Willy Brandt, French President Georges Pompidou and Taoiseach Jack Lynch, merged with the economic foundations of the Common Market to form the basis of the contemporary EU. The signature of the Accession Treaty 50 years ago by Jack Lynch and Patrick Hillery in the Palais d’Egmont in Brussels was the culmination of Ireland’s exigent journey from Europe’s periphery to its core, and paved the way for the EEC’s own journey from an economic entity to a political community.

Irish signatures on the Act of Accession, 22 January 1972

[1] Schuman declaration May 1950 (europa.eu)

[2] Keogh - Ireland's membership of the EEC (ucc.ie)