Are We Paying the Price for the Pandemic? An Outlook for Euro Area Inflation

Introduction

As inflation continues to rise in the euro area, with a 5.3% annual increase in inflation recorded in Ireland for November 2021, policymakers, businesses, and citizens are beginning to question whether the current spike in prices is here to stay. During the pandemic to date, forecasts of inflation have significantly underestimated the actual price dynamics that have emerged in the data. Is the euro area headed for a new era of persistent inflation or will the current period of inflation dissipate as policymakers predict? This blog attempts to explore what is driving the current inflationary period and how central banks are likely to respond to this unexpected surge in prices.

Why is the World Experiencing Inflation?

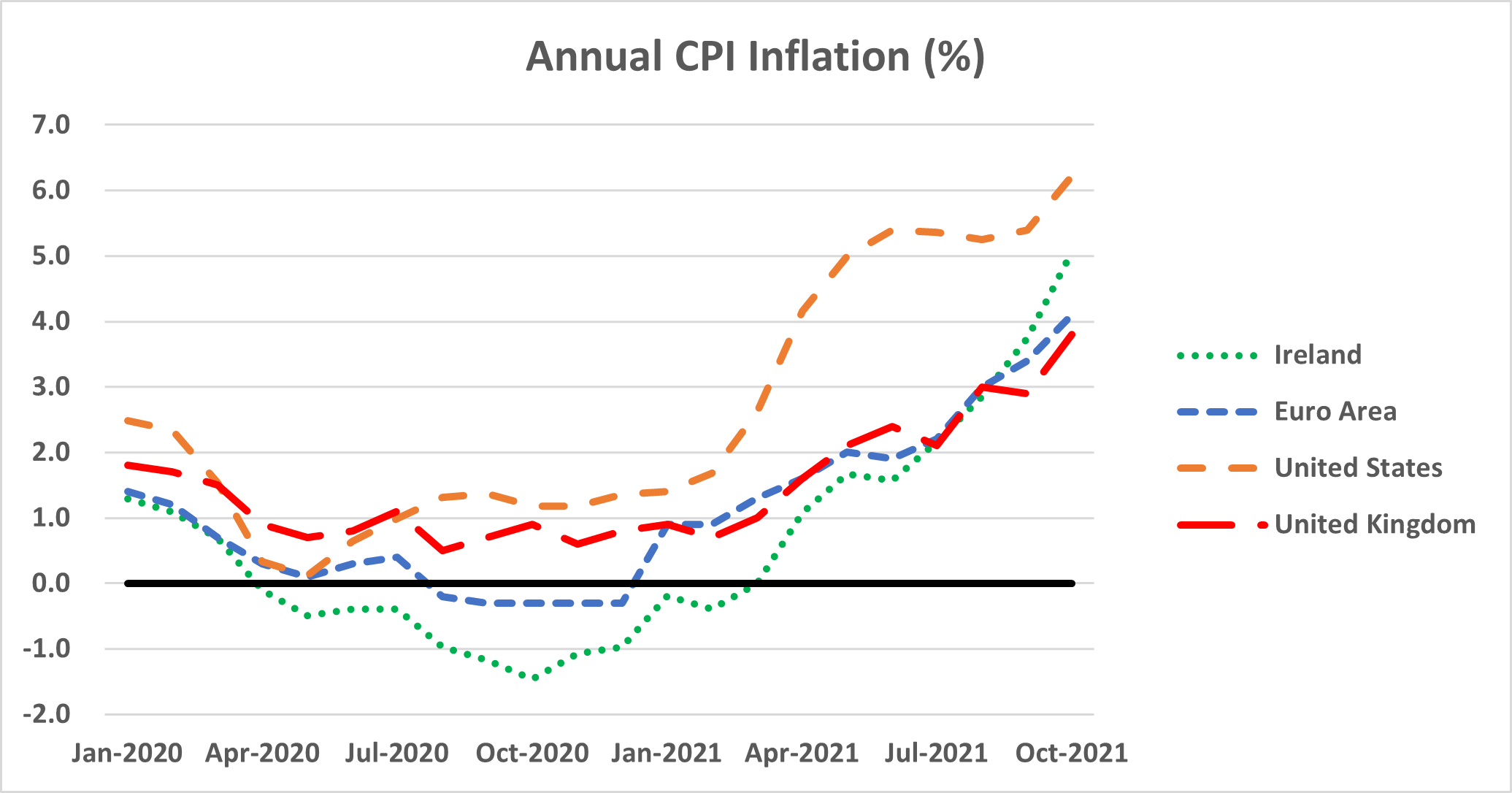

Figure 1. Source: OECD

Inflation has begun to present itself in the euro area, the US, the UK and further afield approximately since the beginning of 2021. The latest figures for inflation in the euro area and the United States reveal a 4.1%[1] and 6.8%[2] annual increase in prices respectively, which is considerably above the European Central Bank (ECB) and Federal Reserve inflation target of 2%. A flash estimate of Eurozone inflation for November 2021 released by Eurostat on Tuesday, 30 November 2021 shows annual inflation continuing to rise at 4.9%.[3]

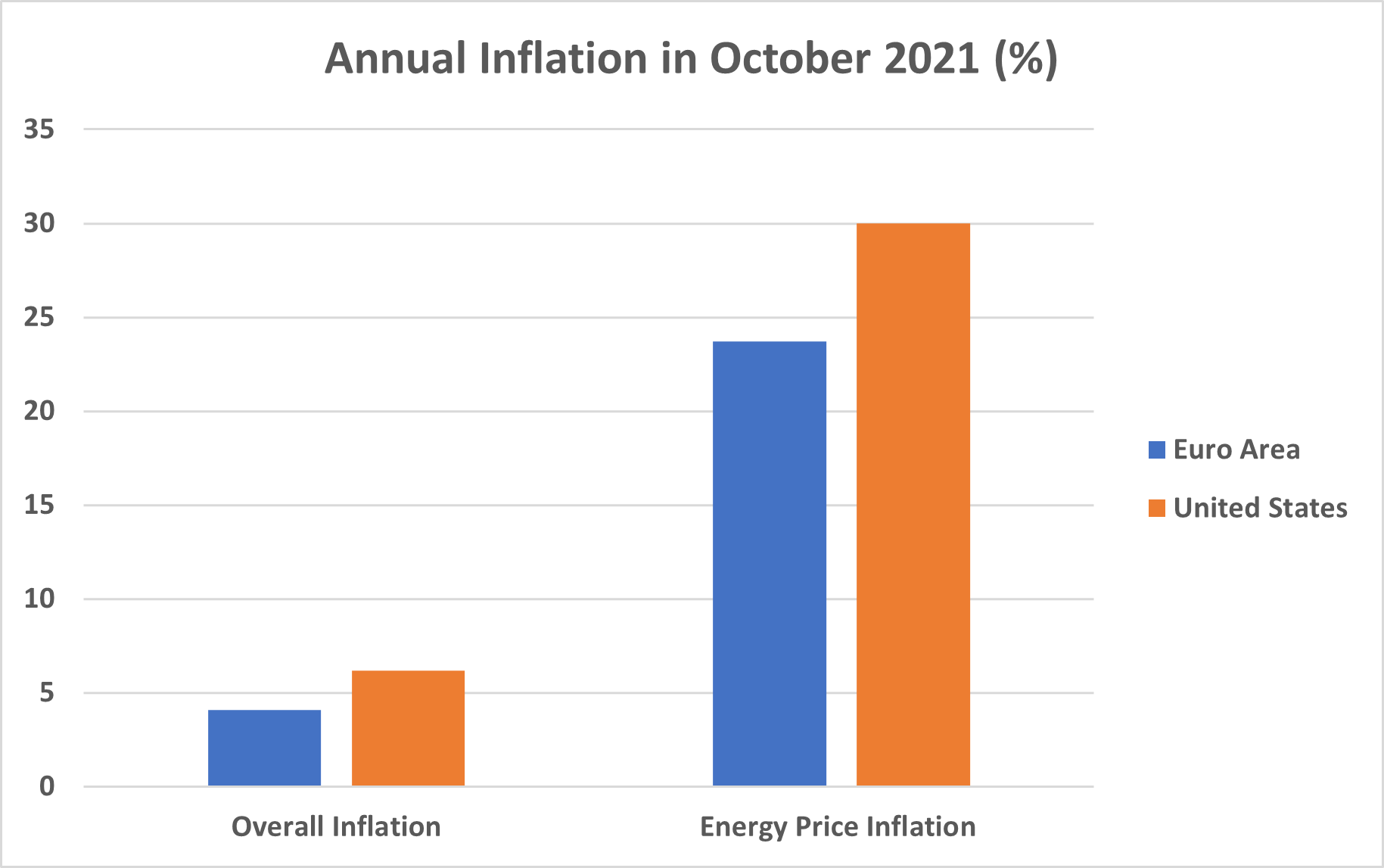

In Ireland, many of us will be acutely aware of the steep price increases in our energy bills over the last number of months and indeed, this has been the case across the euro area and elsewhere, as Figure 2 shows below. Rising commodity prices, such as large increases in the price of oil and natural gas, have led to rising energy costs for consumers and increases in production costs for companies which have been passed onto consumers. Natural gas prices in the EU, which are almost six times higher than at this time last year, have responded to increased demand as well as underinvestment in the supply of gas and less availability of gas reserves in the EU.[4]

Figure 2. Source: Eurostat[5], Bureau of Labor Statistics[6]

In addition, supply chain disruptions due to the impact of the pandemic have also been persistent despite the improving economic outlook around the world. Within its November 2021 Eurozone Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) release, which is derived from surveys of senior executives in private companies in the Eurozone, IHS Markit comments: “Supply delays spiked to a record high in May 2021 and have since continued to deteriorate at rates surpassing anything ever seen prior to the pandemic.” The company believes that the “constriction of output relative to new orders” helps to explain why inflation continues to increase, and that higher producer prices in its November 2021 survey suggest that price pressures will continue.[7]

How is the ECB Thinking About Inflation?

Despite mounting concerns regarding the future trajectory of price increases, central banks have been reluctant to raise interest rates. This is largely due to a belief amongst central bankers and financial markets that post-pandemic inflation will be ‘transitory’ and will return to close to central bank target levels in the coming years.

In July 2021, the ECB also adopted an updated monetary policy strategy after it concluded its Monetary Policy Strategy Review. The new monetary policy strategy details the three conditions required to justify an increase in interest rates:

In support of its symmetric two per cent inflation target and in line with its monetary policy strategy, the Governing Council expects the key ECB interest rates to remain at their present or lower levels until it sees inflation reaching two per cent well ahead of the end of its projection horizon and durably for the rest of the projection horizon, and it judges that realised progress in underlying inflation is sufficiently advanced to be consistent with inflation stabilising at two per cent over the medium term. This may also imply a transitory period in which inflation is moderately above target.[8]

A poll of economists conducted by Reuters from Monday, 18 October 2021 to Thursday, 21 October 2021 suggested that economists do not expect a rate rise by the ECB before the end of 2023.[9] Meanwhile, an account of the ECB’s monetary policy meeting of October 2021 acknowledges the markets are beginning to forecast an increase in interest rates by the end of 2022, which indicates a growing divergence of views on the future trajectory of the ECB’s monetary policy between economists and markets.[10]

In response to growing market fears about sustained inflation, ECB President Lagarde stated on Wednesday, 3 November 2021 that it is “very unlikely” that the conditions required to justify an increase in interest rates will be met in 2022,[11] a phrase that she repeated ad verbatim on Friday, 3 December 2021.[12]

In response to the pandemic, the ECB deployed a €1.85 trillion pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), a form of quantitative easing,[13] whereby the ECB conducts asset purchases of government and corporate bonds in the euro area. The ECB announced at its September monetary policy meeting that though it was not unwinding the PEPP, it would conduct asset purchases at a “moderately lower pace” than in the first two quarters of 2021.[14] At its December monetary policy meeting, it is likely that the ECB will announce the unwinding of the PEPP, which is due to conclude in March 2022.[15]

A key question surrounding the future of the ECB’s monetary policy will be the extent to which it continues to pursue quantitative easing in response to rising inflation. The ECB currently purchases approximately €60 billion worth of bonds per month under the PEPP and €20 billion per month under its regular asset purchase programme (APP). A poll of economists by Reuters in December found that the median forecast of economists was for an unwinding of the PEPP, and an increase in APP asset purchases of €20 billion per month. This would therefore equate to €40 billion a month of asset purchases, or a halving of the ECB’s total asset purchases.[16]

In summary, despite the upward pressures on prices, and the recent announcement of 6% inflation in Germany for November 2021,[17] the ECB has remained firm in its view that the current increase in inflation is ‘transitory’ and has not provided any indication that it has plans to increase interest rates in the near future. The ECB is therefore placing its bets that the current spike in prices will level off in 2022 and 2023. However, President Lagarde also offered reassurances that the ECB would “stand ready” should inflation expectations indicate a more sustained higher period of inflation over the medium-term.[18]

The question naturally follows of what should cause central banks to worry that transitory price pressures will become more sustained and how policymakers can ascertain whether the world should expect a continued spiral in prices.

Are Higher Prices Here to Stay?

Economists consider the idea of inflation expectations to be important in determining how prices fluctuate in the short to medium term. If consumers and businesses expect permanently higher prices in the future, they will purchase goods and services today to capitalise on lower prices, which in turn creates a self-reinforcing demand-led increase in prices in the future. Hence the notion of ‘anchored inflation expectations’ is important in preserving price stability and is a fundamental policy goal of central banks.

As such, it makes sense to consider whether there has been an ‘unanchoring’ of inflation expectations in the past year. The evidence would suggest that, overall, this has not been the case in the euro area.

The ECB conducts surveys of professional inflation forecasters each quarter and these surveys reveal that forecasters broadly expect inflation to remain on target in the years ahead, with the survey for the fourth quarter of 2021 forecasting a mean estimate of 1.9% for 2022, 1.7% for 2023 and 1.9% five years from now.[19]

Furthermore, the five-year inflation forward swap, a key metric that the ECB uses to track market expectations of future inflation, as of Wednesday, 1 December 2021, implies a 5-year average inflation rate that is below 2%.[20] As such, neither forecasters nor financial markets expect medium-term inflation to deviate considerably from the ECB’s 2% objective.

A second source of possible sustained inflation over the coming decade could take the form of a ‘wage-price spiral’. In this possible scenario, existing upward price pressures since the pandemic began lead employers to increase employee wages in the labour market. Due to greater purchasing power and higher demand, firms then charge more for goods and services, which creates a price spiral.

For this scenario to be plausible, there would need to be evidence of above trend wage increases since the pandemic began. However, despite substantial reductions in unemployment across the EU and euro area in 2021, the rate of increase in total EU and Eurozone labour costs declined during the first and second quarters of 2021 according to Eurostat’s labour cost index. In the euro area, labour costs fell on an annual basis by 0.1% in the second quarter of 2021.[21]

It also makes sense to consider the demand side impact of increased household savings during the pandemic on inflation. Within the euro area as a whole, the household savings rate grew from 13% in 2019 to over 19% in 2020.[22] Data from Eurostat suggests that while household incomes are similar to pre-pandemic levels, there was a very strong rebound in consumption in the third quarter of 2020. In the second quarter of 2021, household real consumption per capita increased by 3.1%, while the household savings rate declined by 2.6%.[23] This rebound in consumption associated with spending of increased savings as the economy reopens would suggest a temporary period of increased inflation in the euro area.

Conclusion

Taken holistically, the contents of this blog provide a justification of the ECB’s stance on the question of inflation and suggest a more temporary period of higher prices post-pandemic. These temporary price pressures will be unlikely to emulate the conditions which resulted in extended periods of high global inflation in the past, particularly during the 1970s.

However, given the Herculean task of correctly forecasting inflation, the emergence of several concerning trends particularly in relation to supply chains, the uncertainty of the new Omicron COVID-19 variant, and the higher-than-expected inflation to date, the path ahead for the future of post-pandemic inflation is far from certain.

Overall, it would appear that, for now, the euro area is indeed paying the price for the pandemic. How high a price that is, however, is still to be determined.

[2] https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cpi.nr0.htm

[6] https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cpi.nr0.htm

[9] https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ecb-raise-rates-2024-risk-remains-earlier-hike-2021-10-22/

[10] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/accounts/2021/html/ecb.mg211125~ca9833f9a9.en.html

[11] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2021/html/ecb.sp211103~d0720ef27b.en.html

[12] https://www.ft.com/content/dfd205bd-bb19-46f2-9a75-47af00a843b5

[13] Quantitative easing is a tool which has been used extensively by central banks since the COVID-19 crisis whereby central banks purchase bonds with the goal of increasing money supply, stimulating lending in the real economy by lowering interest rates, and thereby creating economic growth.

[14] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2021/html/ecb.mp210909~2c94b35639.en.html

[15] https://www.rte.ie/news/business/2021/1130/1263983-euro-zone-inflation/

[16] https://www.reuters.com/article/eurozone-economy-poll-idUSKBN2IS00V

[17] https://www.ft.com/content/5933f31b-605b-459a-a221-59ae84685457

[18] https://www.ft.com/content/dfd205bd-bb19-46f2-9a75-47af00a843b5

[20] http://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/2014/12/15/1047530ee9.htm

[21] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Labour_cost_index_-_recent_trends

[22] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/bookmark/7eba9261-6c0b-4d44-ad8e-08e43f84ff8c?lang=en