Called to Account? The Permanent Five and the Veto

Introduction

On 26 April 2022, the 193 members of the United Nations General Assembly adopted, by consensus, a landmark resolution (document A/77/L.52) which aims to hold the five Permanent Members of the Security Council accountable for their use of the veto. The resolution, which is entitled, “Standing mandate for a General Assembly debate when a veto is cast in the Security Council”, was co-sponsored by 83 member states, reflecting broad cross-regional support. Of the five Permanent Members, France, the United Kingdom and the United States co-sponsored the resolution, whereas China and the Russian Federation did not. The resolution, proposed by Christian Wenaweser (Liechtenstein) over two years ago, is a separate endeavour from the ongoing intergovernmental negotiations on Security Council reforms.

The text of the current resolution reflects growing concern that the Security Council is encountering challenges in carrying out its responsibilities as mandated under the Charter of the United Nations and the increased use of the veto is a clear expression of these challenges.

Under Article 24 of the UN Charter, the Security Council’s primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security was conferred on it by member states of the United Nations, who acknowledge that in carrying out its duties the Security Council acts on their behalf.[1] The latest resolution sends the clear message that where the Council is hindered from carrying out its functions, the membership of the United Nations as a whole, should be given a voice.

To Veto or Not to Veto?

The power of veto afforded to the five permanent Security Council members, China, France, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States, derives from Article 27 (3) of the UN Charter, which establishes that all substantive decisions of the Council must be agreed unanimously.[2] The veto power is the key distinction between the permanent five members of the UN and the ten rotating non-permanent members, and is among the topics most frequently raised in debates about reform of Security Council working methods.

The most contentious debates at the inception of the United Nations concerned the veto, when a number of states expressed explicit concerns about a veto power being conferred upon the Permanent Members of the Security Council. As far back as the San Francisco Conference in 1945, Australian Foreign Minister, Herbert Vere Evatt, argued that the veto should not apply to cases relating to the peaceful settlement of disputes. However, the great powers stood firm and stated clearly that their participation in the UN, and indeed the success of the San Francisco Conference, was contingent on the power of veto being conferred on them, for all matters other than procedural issues.

Since then, the use of the veto has frequently been criticised, particularly as Permanent Members have repeatedly used the veto to quash measures that are contrary to their own national interests, (for example, between 1972 and 2022, the US vetoed 44 Security Council resolutions that were critical of its ally, Israel). It is widely acknowledged that the use of the veto, or threat of the veto, is at times instrumentalised to the detriment of international peace and security.

The Hidden Veto

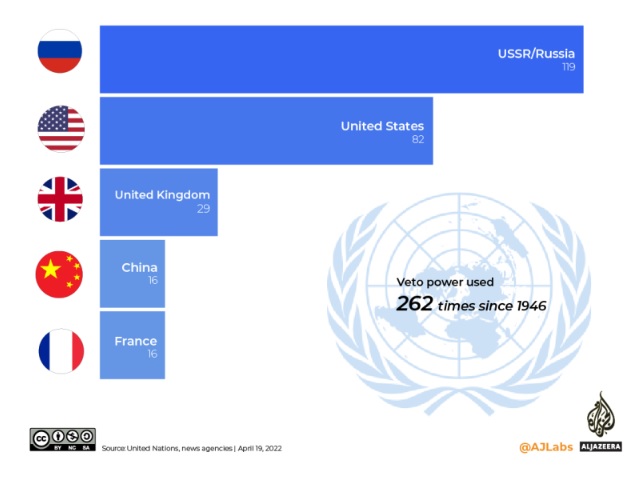

There are certain procedural anomalies regarding the use of the veto. Since 1946 the veto has been used a total of 262 times, moreover, it is not unusual for a draft resolution not to be formally tabled by a member where there is a high likelihood that the veto will be used by one or more Permanent Members. Therefore, it is difficult to assess the true effect of the veto on Security Council activities. A paper trail exists only if a draft is produced as a Council document, which in most cases occurs only when there is a reasonable expectation of adoption. This “hidden” veto undermines the effectiveness of the Council and contributes to a lack of transparency.

Previous Initiatives

Two other initiatives were previously proposed with regard to the use of the veto, specifically in the case of mass atrocities.

In 2015, the UN Accountability, Coherence and Transparency Group proposed a “Code of Conduct regarding Security Council action against genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes,” calling on all members of the Security Council (both permanent and elected) to not vote against any credible draft resolution intended to prevent or halt mass atrocities.

In 2020 France, together with Mexico, put forward a political declaration, which was signed by 105 member states, introducing a proposal for the five Permanent Members of the Council to suspend the use of the veto in the event of mass atrocities, crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes.

Now, in April 2022, the General Assembly has adopted its resolution to prevent the use of the veto from being the last word on crucial issues of peace and security.

The Current Context

The General Assembly resolution (document A/77/L.52) has been passed at a time when the Security Council remains paralysed in the face of the biggest risk to international peace since World War II. There is a sense among the wider UN membership that the veto has time and time again debilitated the Council in cases of the most egregious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law. A divided Security Council has been unable to mount effective responses to recent crises across the globe, including in Gaza, in Darfur, in Syria and in Ukraine.

On 25 February 2022, Russia vetoed a resolution in the Security Council which would have condemned Russia’s unprovoked aggression against Ukraine and called on Moscow to withdraw. It is widely accepted that the Russian Federation egregiously violated the Charter when it invaded Ukraine in February, and then blocked the Council’s ability to address the situation. This move demonstrates that the Security Council will be unable to take any concrete measures against Russia, including a referral to the International Criminal Court which has jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute the crime of aggression. This has triggered widespread criticism of the Security Council’s working methods.

Image sources, Reuters

On the other hand, a week later in the UN General Assembly, 141 member states voted in favour of a resolution demanding an immediate halt to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, while only 5 states voted against (Belarus, the DPRK, Eritrea, Russia and Syria), thus sending a clear message of international solidarity with Ukraine.

Implications – The Future of the Veto?

The newly adopted resolution provides for the General Assembly to be convened by its President, (currently Abdullah Shahid), within ten working days of the casting of a veto by any of the Permanent Members. The purpose of this meeting would be to hold a debate on the situation as to why the veto was cast.

The resolution is criticised as having no teeth, as the text of the resolution is non-binding, and a Permanent Member that has used its veto may decline to explain its actions to the General Assembly. Furthermore, the General Assembly is not required to take or consider any action. However, supporters of the resolution are hopeful that it will encourage transparency and accountability, while deterring overuse of the veto, whereas critics of the resolution have warned that it may divide the UN even further.

Those who are apprehensive about the new initiative have argued that it is superfluous because Permanent Members of the Security Council often provide an ‘Explanation of Vote’, when the veto is used, to clarify why it was cast. However, others contend that the mandate of the General Assembly to convene a debate after the casting of a veto could be a complementary and inclusive exercise, rather than duplicative and will provide a platform where the voices of all 193 members of the General Assembly can be heard, ultimately strengthening multilateralism within the organisation.

That said, the General Assembly cannot become a judge of the Security Council, as Article 12 of the UN Charter stipulates that the Assembly cannot discuss and make recommendations on peace and security matters which are at the time being addressed by the Security Council.[3] Some member states have suggested that the new resolution may therefore cause procedural confusion and inconsistency in practice.

A further argument raises doubts about the efficiency of the resolution in deterring overuse of the veto by the Permanent Five. On the other hand, champions of the resolution believe it will raise the political cost of wielding the veto, which is an important consideration for some members of the Council. While Russia and the US have historically shrugged off criticism of their vetoes, China, the most reticent of the Permanent Members on the subject of veto reform, is more likely to be wary of potential political implications.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the creation of this new procedure does not eliminate or otherwise modify the existing veto, as that would require an amendment to the UN Charter. This is an unlikely outcome, as any amendment is required to be “adopted by a vote of two thirds of the members of the General Assembly and ratified in accordance with their respective constitutional processes by two thirds of the members of the United Nations, including all the Permanent Members of the Security Council”, according to Article 108 of the Charter.[4]

The irony of the current situation is that the impetus to establish the United Nations largely stemmed from the inability of its predecessor, the League of Nations, to prevent the outbreak of the Second World War, and from the outset the Preamble to the Charter of the United Nations sets out its purpose “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war”.[5] As the world watches in fear of World War III in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the use of the veto is perceived to be holding the Security Council hostage. While the latest resolution is ultimately a transparency mechanism, which may at first glance seem like a modest initiative with modest outcomes, it is also a step towards meeting the legitimate demands of member states that the Security Council be accountable to those on whose behalf it acts.

[1] Article 12, The Charter of the United Nations.

[2] Article 108, The Charter of the United Nations.

[3] Preamble to the Charter of the United Nations.

[4] Article 24 (1), The Charter of the United Nations.

[5] Article 27 (3), The Charter of the United Nations.